E.R. Shipp Special to USA TODAY

Published 6:11 PM EST Feb 8, 2019

After having been kidnapped from their villages in what is present-day Angola, forced onto a Portuguese slave ship bound for what Europeans called the New World and stolen from that ship by English pirates in a confrontation off the coast of Mexico, “some 20. and odd Negroes” landed at Point Comfort in 1619, in the English settlement that would become Virginia.

Their arrival was duly noted by the colony’s secretary, John Rolfe, famous as the widower of the Native American woman called Pocahontas.

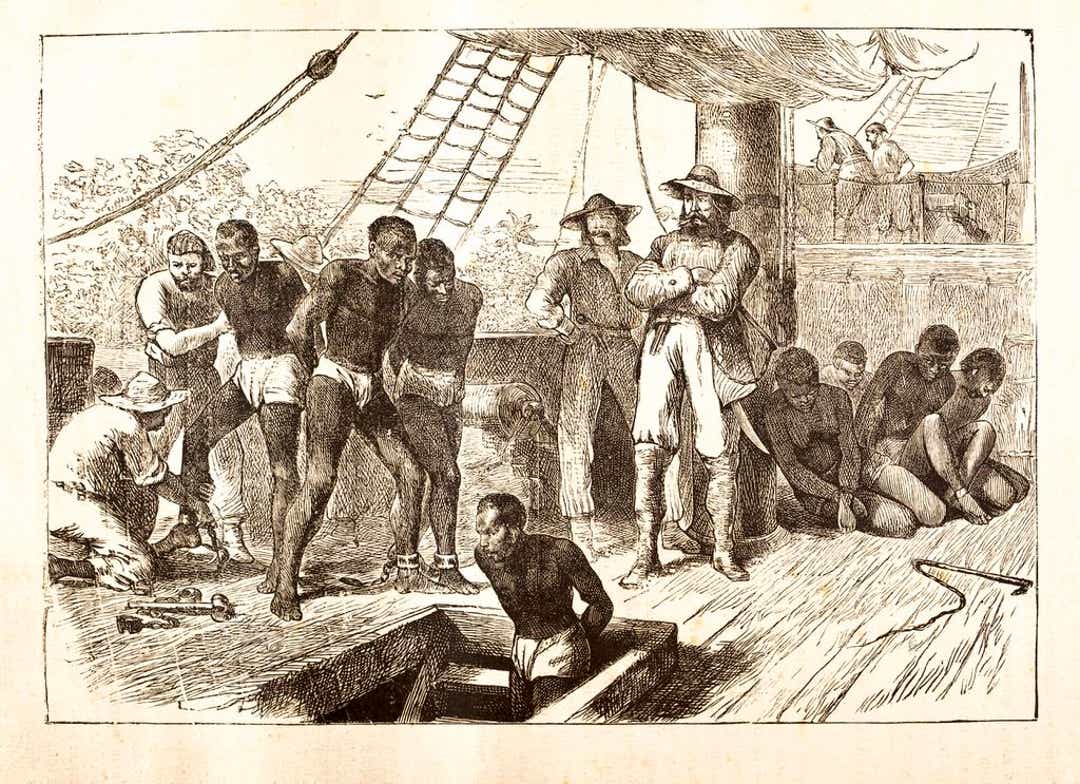

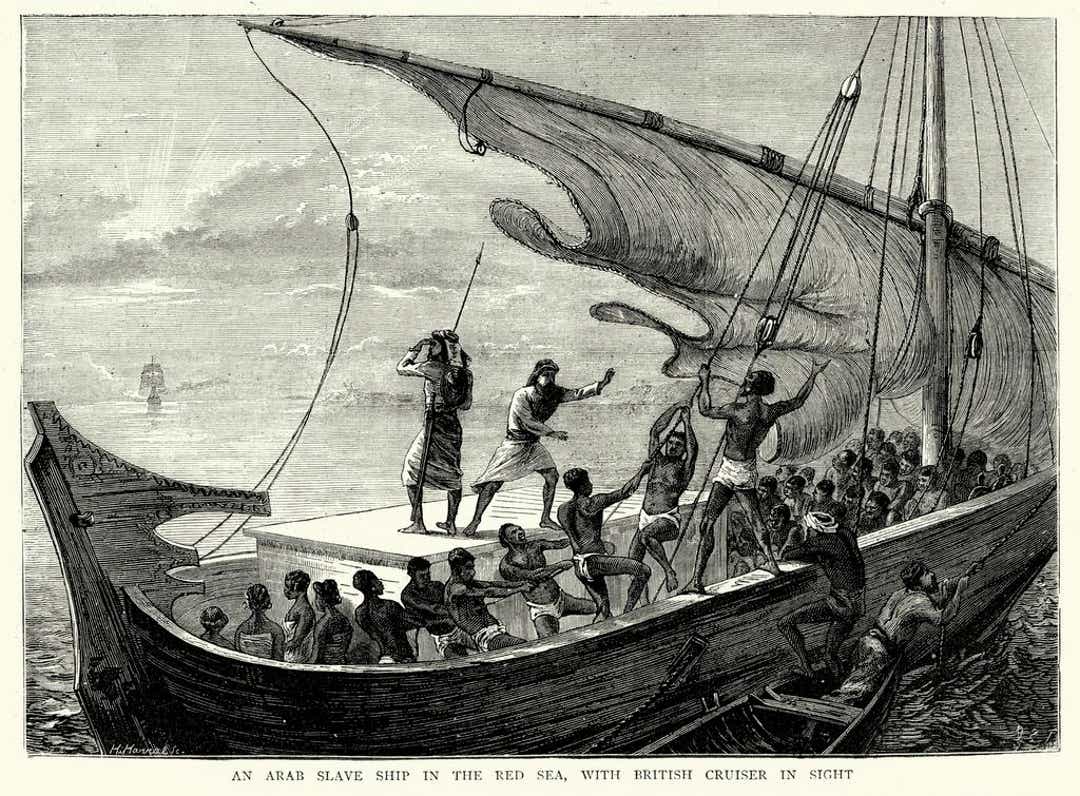

The harrowing journey that began with about 350 Africans on board the San Juan Bautista was one of terror, hunger and death even before the encounter with the pirates. About half of the Africans who boarded the Portuguese ship died, some of the millions who perished during the Middle Passage from the 1600s to the 1800s. When the San Juan Bautista docked near what is now Veracruz, Mexico, on Aug. 30, 1619, there were 147 Africans on board. Fifty had been taken by those English pirates aboard two ships, the White Lion and the Treasurer.

When the White Lion arrived unheralded in Point Comfort, the captain’s immediate task was to sell the Africans in exchange for food.

“Few ships, before or since, have unloaded a more momentous cargo,” historian and journalist Lerone Bennett wrote in his 1962 book, “Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in America.” (The subtitle was changed in later editions to “The History of Black America.”)

For many black readers, accustomed to being told in myriad ways that blacks had no history, the notion that their ancestors’ presence in America predated the 1620 arrival of the Pilgrims story was a mind-boggling revelation. Bennett provided an origin story to embrace.

The 400th anniversary of the Africans’ arrival in what is now the USA is being observed this year. The Association for the Study of African American Life and History, the custodian of Black History Month, is taking the lead in paying tribute to perseverance and resilience. Congress established the 400 Years of African-American History Commission. And for more than two years, the Hampton 2019 Commemoration Commission and Virginia’s “2019 Commemoration, American Evolution” have sponsored programs that highlight not just the arrival of Africans but also other significant developments in the state’s – and the nation’s – history, including the establishment of the first representative legislative assembly in the New World.

Why is that 1619 arrival in Virginia so noteworthy when, as Bennett wrote and scholars are still explaining, it was but one of the points of arrival of blacks in the New World? More than a century before, blacks had accompanied Spanish and Portuguese explorers on expeditions in North and South America. Africans may have accompanied Sir Francis Drake when he arrived at Roanoke Island in 1586, attempting but failing to establish a permanent English colony.

And while some declare that 1619 marked the beginning of slavery in England’s American colonies, they are off the mark in at least two ways. First, Africans had been imported as slave labor in the English colony of Bermuda before 1619. Second, the status of those “20. and odd Negroes” from the White Lion is still a matter of contention.

“The 1619 story is only important for the people who develop within the nation state that becomes known as the United States,” notes Daryl Scott, a professor of history at Howard University in Washington and a past president of Association for the Study of African American Life and History. “It’s about how you define the history that you’re telling.” He points out that if one were to consider the migration of Africans from about the 15th century, one could also mark arrivals in Spain, Portugal and Italy, as well as in the Arab world.

“There is a tendency to simplify our story, to have a definitive start and end date, to say that slavery began on this day, when we actually don’t know; to say that black people arrived on this date so that we can mark it,” says Karsonya Wise Whitehead, a professor of communication and history at Loyola University Maryland. “That’s part of being American. We like to mark things. But our history is more complicated than that.”

Nothing is more complicated than sorting out who those “20. and odd Negroes” were, what their status was in the settlement, and what became of them.

We know that the Africans who arrived in 1619 on the White Lion (and, a few days later, the Treasurer) were from Angola, and we know how they came to be captured. We don’t have all the names, but we do know that captain William Tucker took two of them into his household, Isabella and Antony, and allowed them to marry. When their child William became the first recorded black birth in what would become the USA, he was baptized into the Anglican faith in 1624. We know that a “Negro woman” named Angelo in a 1624 census had arrived on the Treasurer in 1619. Archaeologists have recently discovered graves that might include hers.

“This first group that came survived and created a solid and growing community of people of African descent, with some of them intermingling with English and the Native peoples,” says Cassandra Newby-Alexander, a professor of history at Norfolk State University and a member of various commemoration commissions. Over a few decades, she said, the African presence grew with the arrival of more ships as well as with births. This resulted in “the emergence of racialized politics, law and a bifurcated society.”

How the Virginians viewed the Africans is a subject of robust debate. The practice of indentured servitude was longstanding among the English. That’s how many whites began life in the New World, providing labor for a set number of years. At the end of their contracts, they received “freedom dues” of food, clothing and maybe even a parcel of land. But the Africans?

“It’s rather clear that Virginia did not have a set way of dealing with these folks, and it got worked out over time,” Scott says. “They had indentured people in Virginia, and some people may have seen Africans just like they saw other indentured people. We know some people became free, so it looks like they were treated like every other indentured person.”

Other scholars, including Linda Heywood and John Thornton of Boston University, insist that the Africans from the White Lion and the Treasurer were enslaved by the English as they had originally been by the Portuguese slave traders before they were taken by pirates.

Whether indentured servants or slaves, Newby-Alexander says, “Either way, they were unfree.”

Some of the early Africans, like Anthony and Mary Johnson, who arrived in 1621 and 1622, respectively, amassed hundreds of acres of land and owned slaves themselves. Some won their freedom in court; others, like John Punch, were sentenced to permanent servitude for daring to run away.

By 1705, any ambiguity about the status of blacks – free, indentured, enslaved – was clarified by a series of so-called racial integrity laws that institutionalized white supremacy.

So the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the White Lion is “a little bit of a celebration, a little bit of a commemoration, a little bit of reflection – and a lot of wrestling with ‘what does this mean?’” Whitehead says.

E.R. Shipp, winner of the 1996 Pulitzer Prize for commentary, is a founding faculty member of the School of Global Journalism and Communication at Morgan State University in Baltimore.

Recent Comments